- Research

- Open access

- Published:

Challenges to conducting research on oral health with older adults living in long-term care facilities

BMC Oral Health volume 24, Article number: 422 (2024)

Abstract

Background

The challenges to conducting oral health studies involving older people in long-term care facilities (LTCFs) must be debated.

Objective

This study aimed to investigate researchers’ perceptions and experiences while conducting an epidemiological survey on oral health among older individuals residing in LTCFs.

Methods

A qualitative study was conducted involving six researchers who utilized field diaries to record their impressions during data collection through interviews (older individuals (or their proxies), caregivers, and LTCF coordinators) and oral examinations of the older people participants. Additionally, researchers responded to open-ended questions about their experiences. The collected material was subjected to content analysis by two researchers.

Results

The themes that emerged from the analysis were institutional context, aspects affecting the operationalization of the study, and data collection oriented by the clinical-functional profile of the older people. According to the researchers’ perceptions, LTCF coordinators demonstrated concern for the study’s benefits for older adults and the preservation of institutional routines during the research process. Caregivers emerged as vital sources of information, guiding researchers in navigating the challenges posed by the physical and mental complexities of the older people participants, necessitating empathy, sensitivity, and attentive listening from the researchers. The organization of materials and a streamlined data collection process proved essential for optimizing time efficiency and reducing stress for participants and researchers.

Conclusion

The researchers recognized the important role played by LTCF coordinators and formal caregivers, underscoring the significance of empathetic methodologies and streamlined data collection processes in mitigating the challenges inherent to research conducted within LTCFs.

Background

Population aging is a global phenomenon presenting significant challenges to healthcare systems worldwide due to the burden of chronic age-related conditions [1]. The aging process often leads to frailty and increased functional dependence, resulting in a notable rise in institutionalization [2]. In Brazil, as observed in other countries like the United States, France, and China, the age pyramid has undergone an inversion, contributing to a higher prevalence of chronic diseases and functional dependence among older individuals. Consequently, the population residing in long-term care facilities (LTCFs) has grown substantially [3,4,5].

Older adults living in LTCFs generally depend more on daily activities than their non-institutionalized counterparts, and oral health is a prominent concern [6, 7]. Institutionalization can negatively impact older individuals eating habits, cognition, and overall functioning, resulting in deteriorating health conditions [6, 8]. Furthermore, significant barriers to oral health care exist within nursing home settings [9, 10]. The oral health of this group is characterized by severe tooth loss, oral diseases, and biofilm accumulation [11,12,13]. These conditions have been associated with adverse outcomes in terms of general health, quality of life, and mortality [14]. In Brazil, the operations of LTCFs are regulated by the National Vigilance Agency. However, despite the recognized need to improve oral health care provision in these institutions, the regulations do not explicitly address oral health. Therefore, research in LTCFs is imperative to generate robust scientific evidence concerning the oral health needs of older individuals. Such evidence is essential for enhancing standards of care and making informed decisions that prioritize the overall health and well-being of older populations. A recent review analyzing barriers to translating research into oral healthcare policy and practice for older adults stressed the need for increased efforts to undertake research involving older adults, including frail older adults living in residential care, to develop an evidence-informed paradigm for oral health care and expand policies and care practices for this age group [15].

However, conducting studies involving older people in LTCFs poses numerous challenges, demanding meticulous planning, considerable time, and ample resources to overcome these obstacles [16]. Nevertheless, there is a lack of research discussing these challenges [17,18,19], particularly strategies to include older individuals with dementia in studies [20, 21]. Although health research may share similar challenges, none of these studies have discussed research experiences, including oral health assessment. The previously reported challenges were related to obtaining consent, conducting interviews, engaging caregivers and family members, maintaining privacy, addressing participant attrition, obtaining sufficient sample sizes, accounting for intra-institution cluster effects, dealing with incomplete data, and navigating rigid LTCF practices and routines [16,17,18,19,20,21]. For older individuals with dementia, researchers emphasize the need for inclusive strategies, considering their communication difficulties, memory loss, diminished autonomy in decision-making, and emotional disposition [20]. The only identified systematic review on methods for involving older people in health-related studies highlights the viability of studies involving older adults, emphasizing the importance of clear communication, building good relationships, and employing flexible approaches [22].

This study aimed to investigate researchers’ perceptions and experiences while conducting an epidemiological survey of oral health among older individuals residing in LTCFs. The findings of this study can provide a valuable understanding of the challenges faced during the study and identify effective strategies to improve the quality and efficiency of future research in this context. Furthermore, understanding researchers’ perspectives makes it possible to develop specific recommendations to enhance research methods for this vulnerable population. By addressing these challenges and designing effective strategies, this research can improve the quality of studies focusing on older populations living in LTCFs and promote evidence-informed oral healthcare policies and practices for this age group.

Methods

This study employed a qualitative method with a phenomenological approach to explore the experiences of researchers during data collection with older individuals residing in LTCFs and their perceptions of the execution of this work. The phenomenological approach, centered on language, seeks to capture the essence of the lived experience and the emergent meanings from that experience. Previous knowledge of the phenomenon is disregarded to explore how the subjects experience events [23, 24]. Field diaries and an online form with open-ended questions were used to explore the researchers’ experiences.

Context of study

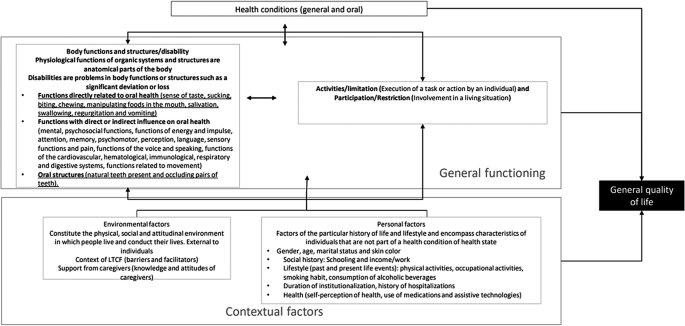

The research was conducted at philanthropic LTCFs in Belo Horizonte, Brazil, during a cross-sectional study between August 2022 and March 2023. In 2022, there were 28 philanthropic LTCFs in the city. The sample planning aimed to include all older individuals residing in these facilities, irrespective of their cognitive status. The study participants were coordinators of the LTCFs, formal caregivers of older people, and individuals aged 60 years or older residing in these facilities. The formal caregivers of the older adults were remunerated professionals with employment ties in the LTCFs, having received specific training as elderly caregivers or being nursing technicians. During data collection, they assisted and cared for the older adults. Epidemiological data were collected through interviews with the coordinators, formal caregivers, and older individuals or their proxies (caregivers). The collected variables followed the model of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (Fig. 1), which included anthropometric measures and physical and oral examinations conducted at the LTCFs.

The six researchers involved in the study had undergone prior training for conducting interviews, and four of them received calibration exercises for the oral examinations. All six researchers participated in the data collection process for the epidemiological research. These researchers consisted of both undergraduate dental students and master’s degree graduate students, who formed pairs to serve as interviewers, examiners, and/or assistants (annotators).

A pilot study was carried out at one of the LTCFs participating in the research to ensure the smooth execution of the study. This pilot study allowed for testing the digital data recording tools and refining the sequence and dynamics for conducting interviews and examinations. The pilot study served as a preparatory phase, ensuring the research procedures were well-coordinated and optimized before the main data collection phase.

Procedure and participants

The research utilized a field diary as the primary method to record informal conversations, observations of the behavior of older people and formal caregivers during data collection, reflections on the examination process and methods employed, as well as the researchers’ impressions regarding the data collection process within the LTCF setting [25, 26]. Researchers independently and freely made digital-format entries in their respective field diaries.

All six researchers independently and freely made digital-format entries in their respective field diaries. Criterion sampling was the method utilized for selecting this sample, which encompassed all researchers who have shared an experience, yet exhibit variations in characteristics and individual experiences [27]. In addition to the field diary, an online form with open-ended questions was employed to collect individual feedback from each researcher about their feelings and experiences as a researcher during the fieldwork. The form included the following guiding questions: (1) How was your experience collecting data at the LTCFs, considering the older people, caregivers, and LTCF context? (2) What was the most striking aspect during the days you collected data at the LTCFs? (3) If you were to advise a researcher about beginning data collection at a long-term care facility through interviews with older people, what observations would you share to ensure their success? (4) what is the main aspect that should be considered for satisfactory data collection with older people similar to those encountered at the LTCFs? The responses to these questions contributed to the researchers’ reflections and perspectives. They were considered part of the corpus of analysis for the study.

Data analysis

The contents of the field diaries and open-ended questions were independently submitted to exhaustive readings by two researchers with experience in qualitative studies for a more in-depth capturing of the information. Subsequently, the data underwent content analysis, following the approach proposed by Graneheim and Lundman [28]. The researchers identified units of meaning within the records and extracted the essence of each unit, resulting in the creation of condensed units of meaning. Through this process, categories and themes that emerged from the analyzed content were identified. Reliability was ensured through continual discussion of the data with the team. Consensus meetings were held to ensure agreement on the themes that emerged. In the final analysis, codes such as R1, R2, and so forth were used to represent each of the interviewees, allowing for a systematic and organized representation of the participants’ contributions.

Ethical aspects

This study received approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. The participants signed a statement of informed consent.

Results and discussion

The data collection for the epidemiological study on oral health assessment in 14 LTCFs, 311 older people, and 164 formal caregivers involved six researchers. They recorded their observations in field diaries and responded to open-ended questions. Through content analysis of the field diaries and open-ended questions, three main themes emerged: (1) institutional context, (2) aspects affecting the operationalization of the study, and (3) data collection oriented by the clinical-functional profile of the older people. The categories under each theme are presented in Table 1.

Institutional context

Results regarding the institutional context are presented in Table 2, showcasing the units of meaning that illustrate the categories within this theme. The researchers recognized the crucial social role played by LTCFs in reintegrating older people, particularly those who have experienced neglect or loneliness, perceiving these institutions as mandated by Brazilian legislation to care for and support older individuals [29]. Regarding the ambience of LTCFs, the study revealed a wide variation in the activities and services offered to residents across different institutions. As stipulated by the Brazilian Resolution, LTCFs should provide a welcoming environment that upholds older people’s human rights and dignity, including aspects such as identity, freedom of beliefs, freedom to come and go, privacy, and respect [30]. The ambience also encompasses fostering family and community involvement in caregiving, the coexistence of residents with different degrees of dependence, supporting residents’ autonomy, promoting leisure opportunities, and preventing violence or discrimination against residents [29]. The Brazilian regulation also standardizes structural aspects of the LTCFs, human resources, health care, nutrition, washing, processing, and storage of clothing, and cleaning facilities [29]. The researchers’ perceptions indicated the importance of establishing systematized assessment processes to reveal the different levels of quality of the LTCFs, indicating the need for policies that favor achieving the principles of ambience and the well-being of the older people who reside in these facilities.

The profile of the older people living in the LTCFs, as recorded by the researchers, was characterized by high frequencies of cognitive impairment, clinical-functional frailty, mental and behavioral disorders, and dependence in performing basic and instrumental activities of daily living. These characteristics posed challenges during the data collection process, as many participants exhibited refusal, resistance, and low levels of cooperation with the study due to their health conditions. This clinical-functional profile is similar to that described for older people living in long-term care facilities worldwide [8, 14]. The researchers also observed rapid functional decline among the older people during the data collection period when the same individuals were visited on different occasions from one week to the next. As a cross-sectional study, the researchers sought to conclude data collection in the first and only approach to older people, whenever possible.

Moreover, fluctuating interest in participation necessitated additional attempts to secure their involvement due to emotional and health-related fluctuations. A previous study involving older people with dementia found that verbal communication varied between weeks, from one day to another, and even within the same day [20]. Another challenge was dealing with the losses of individuals. Data collection began with mapping all residents at the institution by consulting the records. When seeking older people for interviews, there were cases of death – either recent or longer ago. In the latter case, it was perceived that the LTCFs did not perform regular updating and the separation of records.

Regarding oral health, the researchers identified a precarious situation among older people, with a high frequency of tooth loss, caries, and periodontal disease in the remaining teeth, along with unsatisfactory dental prostheses and accumulation of biofilm and dental calculus. This oral health profile aligns with previous studies in different countries, highlighting the substantial burden of oral diseases among institutionalized older individuals [13, 31, 32]. This researchers perception reflects the oral health profile of older people living in LTCFs in Belo Horizonte for more than a decade and a half [12], demonstrating that this population is a special needs group requiring oral care improvements [11, 31].

The researchers recorded the difficulty of older people accessing routine oral care, as many depend on caregivers who have an excessive workload, have little time available to perform oral hygiene, do not prioritize it, or are unaware of its importance. A daily routine of oral hygiene during bathing was often observed, as reported in a previous study, in which nurses reported that the teeth of the majority of residents were brushed at least once a day [13]. The researchers’ findings underscore the pressing need for improved oral care for this special needs population, emphasizing the importance of incorporating oral hygiene into routine healthcare practices, promoting oral care initiatives, and providing training for caregivers [13, 33].

Aspects affecting the operationalization of the study

The researchers encountered various challenges related to the operationalization of the study, particularly in gaining the acceptance and cooperation of LTCFs. Results regarding the operationalization of the study are presented in Table 3. The signing of informed consent by the LTCF coordinators proved to be a complex process, with many expressing resistance and skepticism about the study’s potential impact and benefits for the older residents. Some questioned the importance of a study involving individuals at the end of life. The researchers faced concerns about interrupting institutional routines and potential risks to the residents without any direct return. Similar challenges have been observed in studies conducted in the United Kingdom, where the presence of researchers was perceived as intrusive [17]. In compliance with Brazilian legislation on research involving human beings, participation must be consented to clearly and voluntarily with no financial compensation. As experienced by other researchers, flexibility and creativity were needed to justify the importance of the project to generate evidence that reinforces the importance of oral health for this group. It was also essential to emphasize the low risk associated with the participation of older individuals [17]. Establishing a trusting relationship with the coordinators of the LTCFs proved vital for their willingness to participate in the study. The researchers tried to showcase the study’s potential in generating valuable knowledge, organizing academic extension activities tailored to this specific population, and the potential benefits it could bring to enhance resident care. The presence of researchers might have encountered increased resistance during the pandemic, leading to visit cancellations due to concerns about the higher risk of mortality and morbidity from the coronavirus among older people [34].

The study planning at LTCFs should include the time spent on recruitment and the need for different approaches for contact: repeated telephone calls, personal visits, the presentation of documents/written projects, and the joint determination of a data collection timeframe. Researchers should also be prepared to deal with refusals, as occurred in this study when coordinators vehemently refused to participate, stating that they did not have the authorization or that the LTCF was part of a network that did not permit study participation. This challenge shows that building collaborative relationships with LTCFs is essential to understand research concerns clearly and to plan a project involving vulnerable adults jointly [15]. In contrast, the researchers also recorded situations in which the coordinators were receptive to the study, recognizing that it is important to demonstrate the needs of this population, which could result in programs and policies for older people who reside in LTCFs.

The process of obtaining informed consent from the older residents themselves was also challenging, especially for those with severe cognitive impairment. In such cases, consent was given by caregivers or LTCF coordinators acting as guardians of the older people. The issue of consent by proxy and the ability of the proxy to represent the wishes of cognitively impaired adults has been a subject of debate [15]. Several researchers have highlighted the challenges of obtaining informed consent and respecting the autonomy of individuals with dementia [16,17,18,19,20,21, 35]. Hubbard and Maas emphasized the importance of continually monitoring the individual’s desire to participate, even when a proxy provides consent through the interpretation of verbal and nonverbal signs. They asserted that consent is an ongoing process rather than an a priori one-time event, as Crossan & McColgan (1999) mentioned. We encountered similar situations where residents could not provide direct consent. In such cases, the researchers took great care to explain the study and obtain their assent while interpreting their facial expressions and behavior to respect their autonomy and wishes. Despite these efforts, 15 invited older people chose not to participate.

The institutional routines of LTCFs significantly impacted the study execution. Researchers had to consider and respect the schedules and activities of the older residents, leading to adjustments in the data collection timeframe. Additionally, finding suitable times for interviews and examinations was challenging due to the residents’ mobility problems and caregivers’ availability. The researchers had to collaborate with LTCF coordinators to find mutually agreeable time slots while ensuring minimal disruption to the institution and its residents. Finding suitable time slots to conduct interviews was also a significant challenge, as observed in a previous study exploring the perception of dignity among older people residing in LTCFs [19]. The authors of that study emphasized the need to avoid peak activity times, such as meals or regular visits by physicians, and to avoid conducting interviews immediately after an activity, such as lunch, as participants often displayed weariness and lethargy during such periods [19]. To overcome this challenge, the research team collaborated with the LTCF coordinators to agree on appropriate data collection times that did not disrupt the institution’s routines or inconvenience the residents. This required a significant consideration of each location’s availability and the staff’s workload. Other researchers have noted these challenges [17, 19,20,21, 35], especially considering that caregivers are crucial as proxies for older people. Researchers also had to contend with the unavailability of caregivers to answer questions due to their multifaceted responsibilities in caring for many residents. Introducing the study could thus be an additional burden for them, which many might perceive as unwanted.

In addition to respecting the institutional dynamics, the execution of data collection required careful organization by the researchers regarding the selection of data collection location and methods. Many residents faced mobility issues, making moving from one place to another challenging. In some instances, caregivers were unavailable to assist in this task, requiring additional time to reach the most suitable location for the interview or oral examination. Factors such as lighting, privacy, and participant comfort had to be considered during this process. Adapting the data collection process to the specific situation encountered at each LTCF was necessary. Some facilities had designated spaces for the study, while others lacked appropriate areas, leading to examinations being conducted wherever possible, such as in TV armchairs or beds. Previous studies have discussed the need for such adaptations [17, 20]. According to Hall, Longhurst and Higginson, these field situations also posed challenges to maintaining privacy during data collection, which became especially sensitive during oral examinations [19]. The proximity required for oral examinations could generate discomfort, mainly when conducted in the presence of colleagues and staff. Efforts were made to ensure privacy in such situations. Consequently, conducting studies in this context demanded considerable flexibility and reciprocity, considering the limitations and demands of the LTCFs [19]. The researchers were also concerned about biosafety and cross-infection prevention [36], mainly due to the vulnerability of older people to the COVID-19 pandemic. Adhering to strict protocols and protective measures during data collection became essential to safeguard the health of both residents and researchers.

Various measures can be employed to ensure standardization and successful data collection. Providing proper training and ongoing supervision for the researchers is essential. This training should cover all aspects of the data collection process, including interview techniques, oral examination protocols, and ethical considerations. Additionally, it is crucial to ensure that the researchers have access to the minimum necessary resources required for data collection, such as sterilized clinical kits, personal protective equipment, and appropriate data recording tools. A comprehensive manual of norms and standard procedures should be prepared to maintain consistency and adherence to established protocols. This manual should outline step-by-step instructions for each stage of the data collection process, from participant recruitment to data recording and analysis. Regular reference to this manual will help researchers follow standardized procedures and minimize the risk of errors or deviations during the study [37].

The high proportion of older people with cognitive impairment created additional complexities. Variables related to subjective aspects, such as quality of life and self-perception of health, posed challenges since some residents had limited discursive capacity. The researchers utilized validated instruments designed for older adults with adequate cognitive levels but recognized the need for more context-specific tools for individuals with dementia. Challenges to assessing subjective aspects of the lives of older people with dementia have been discussed, considering the lack of validated instruments for this population. There is a debate in the literature on whether data collected from individuals with dementia are reliable due to cognitive impairment [38]. However, more recently, there has been growing recognition that such individuals can express perceptions, needs, and concerns [38, 39], and their subjective experiences should be considered and investigated in studies [20, 39]. Approaches such as structured observation focused on nonverbal communication (facial expressions and body language) and nonstructured observation within the ethnographic tradition have been employed in previous studies to understand the social world of older people [20]. A study assessing quality of life among older people with dementia combined observation with interviews using open-ended questions, and older people were included based on their capacity to communicate verbally in a conversation rather than based on the diagnosis of dementia [20]. The literature describes the need to use multiple (qualitative and quantitative) methods in studies involving individuals with dementia with different levels of verbal communication skills to promote a contextualized, multidimensional assessment [39]. Such approaches should also be considered strategies to understand the quality of life in the context of oral health assessments in future studies and to guide care strategies considering the experiences and wishes of individuals with dementia.

Data collection oriented by the clinical-functional profile of the older people

The researchers revealed that the clinical-functional profile of older people requires differentiated approaches for data collection, particularly the use of relational skills, such as empathy, active listening, patience, sensitivity, and flexibility to deal with different behaviors – ranging from cooperative to resistant individuals. Results regarding the data collection oriented by the clinical-functional profile of the older people are presented in Table 4. Cognitive impairment and levels of cooperation were identified as obstacles to the data collection process, with frequent resistance to the study. The progression of cognitive decline leads to a deterioration of cognitive functions and behavior and mood disorders, including depression, irritability, and aggressiveness [40,41,42].

This profile of the older people also required communication strategies on the part of the researchers, who needed to be direct and clear, often involving the participation of the caregivers. The researchers manifested insecurity, feeling unprepared to understand and deal with older people in some situations. Hubbard, Downs, and Tester [20] suggest that researchers dealing with dementia should be trained as skilled verbal and nonverbal communicators, sensitive to how dementia impacts memory, decision-making capacity, and emotions. Developing strategies tailored to each participant’s unique experiences and listening to their voice is essential. Hall, Longhurst, and Higginson [19] add that researchers must be particularly patient, and the extra time and training for this must be built into the research design. Establishing set protocols for handling various responses ensures uniformity and consistency [19]. Researchers also had to contend with parallel conversations,” where older people spoke about other subjects and extended the conversation. This required employing different communication strategies and striking a balance between listening to the older person and returning to the assessment without causing discomfort [16, 20].

Sensory impairments, such as low visual and hearing acuity, also compromise communication. Hearing impairment is common among older people [43], and there are also high proportions of blindness and vision impairment among residents of LTCFs [44, 45]. Interviews involving older people with hearing impairment were found to be draining, as the researchers needed to raise their voices and repeat questions. This limitation can negatively impact the quality of dialogue and create discomfort for the older person [20].

The researchers highlighted the caregivers’ knowledge in guiding the data collection process according to the clinical-functional profile of the participants. Being familiar with older people and their physical and mental status, caregivers served as valuable mediators, offering insights into effective communication and strategies for dealing with each case. Caregivers of older people perform the functions of accompaniment and care, offering emotional support as well as support in their social interactions, assisting and accompanying routines of personal and environmental hygiene, nutrition, preventive health care, the administration of medications and other health procedures, and assisting and accompanying the mobility of older people in activities of education, culture, recreation, and leisure [46]. Moreover, caregivers also acted as a proxy for older adults with cognitive impairment, providing information about health and daily activities. The researchers recognized caregivers as a source of support during data collection, contributing to a more efficient and enjoyable data collection process by helping identify older people and guiding them to data collection locations.

The research techniques proved suitable and valuable for understanding the researchers’ experiences. The records of these experiences revealed various challenges and strategies in conducting studies involving older people residing in LTCFs, considering the diversity of residents’ profiles and the institutional context. Table 5 presents a synthesis of the main challenges and the strategies employed to deal with them during the data collection process. Additionally, practical aspects have been listed as recommendations for future studies involving this population.

The main limitation of this study was to have restricted the researchers’ records to field diaries and a form with open-ended questions. Verbal manifestations during the interviews could have revealed new or different perceptions from what was recorded. However, all material obtained was analyzed. The information on the forms at the end of the data collection period had similar content to that recorded during the process but was more synthesized and systematized. Thus, these were complementary methods that demonstrated consistency in the perceptions of the researchers’ experiences.

Conclusion

The researchers recognized the important role played by LTCF coordinators and formal caregivers, underscoring the significance of empathetic methodologies and streamlined data collection processes in mitigating the challenges inherent to research conducted within LTCFs. The institutional context significantly influences the planning and execution of research involving older adults residing in LTCFs, particularly those with clinical-functional profiles that necessitate specific tailored approaches. Respecting older adults’ autonomy and establishing effective and respectful communication are fundamental for building trust. Recognizing the caregivers’ knowledge provides valuable understanding for the data collection process. The LTCF willingness to participate in the research reflects their commitment to advancing knowledge in the field while upholding institutional routines and residents’ well-being. Beyond methodological considerations, such as selecting appropriate variables, defining the sample, and employing valid measures, social and cultural aspects of the LTCFs can impact costs, required human resources, and the execution timeline. In conclusion, conducting studies in LTCFs demands careful planning, effective communication, and flexibility to address institutional and residents’ diverse profiles. Collaborating closely with LTCF staff and caregivers is essential for successful data collection and ultimately benefiting this vulnerable population.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

WHO. World health statistics 2020: monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals. 2020. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1547&context=srhreports. Acesso em 5 de agosto de 2023.

Hajek A, Brettschneider C, Lange C, et al. Longitudinal predictors of institutionalization in Old Age. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(12):e0144203. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0144203.

China. Ministry Civil Affairs People’s Republic China. China civil affairs statistical yearbook. China Statistical Publishing House.; 2013. http://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/ndsj/2013/indexeh.htm. Acesso em 5 de agosto de 2023.

Peng R, Wu B. Changes of Health Status and Institutionalization among older adults in China. J Aging Health. 2015;27(7):1223–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264315577779.

de Laffon C, Morley JE, Levy C, et al. Prevention of Functional decline by reframing the role of nursing homes? J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(2):105–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2016.11.019.

Farias I, Sousa SA, Almeida LFD, Santiago BM, Pereira AC, Cavalcanti YW. Does non-institutionalized elders have a better oral health status compared to institutionalized ones? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cien Saude Colet. 2020;25(6):2177–92. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232020256.18252018.

Benksim A, Ait Addi R, Khalloufi E, Habibi A, Cherkaoui M. Self-reported morbidities, nutritional characteristics, and associated factors in institutionalized and non-institutionalized older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):136. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02067-3.

de Medeiros MMD, Carletti TM, Magno MB, Maia LC, Cavalcanti YW, Rodrigues-Garcia RCM. Does the institutionalization influence elderly’s quality of life? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):44–44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-1452-0.

Czwikla J, Herzberg A, Kapp S, et al. Home care recipients have poorer oral health than nursing home residents: results from two German studies. Article J Dentistry. 2021;107103607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdent.2021.103607.

Ferreira RC, Wolff CS, Silami CMd, Nogueira AM. Atenção odontológica E práticas de higiene bucal em instituições de longa permanência geriátricas. Cien Saude Colet. 2011;16. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-81232011000400032.

Ferreira RC, Magalhães CS, Rocha ES, Schwambach CW, Moreira AN. Oral health among institutionalized elderly in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais State. Brazil Cad Saude Publica. 2009;25(11). https://doi.org/10.1590/s0102-311x2009001100008.

Ferreira RC, De Magalhães CS, Moreira AN. Tooth loss, denture wearing and associated factors among an elderly institutionalized Brazilian population. Gerodontology. 2008;25(3):168–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-2358.2008.00214.x.

Saarela RKT, Hiltunen K, Kautiainen H, Roitto HM, Mäntylä P, Pitkälä KH. Oral hygiene and health-related quality of life in institutionalized older people. Eur Geriatr Med. 2022;13(1):213–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-021-00547-8.

Wong FMF, Ng YTY, Leung WK. Oral health and its Associated factors among older institutionalized Residents-A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(21):4132. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16214132.

Allen F, Tsakos G. Challenges in oral health research for older adults. Gerodontology. 2023;00:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/ger.12681.

Zermansky AG, Alldred DP, Petty DR, Raynor DK. Striving to recruit: the difficulties of conducting clinical research on elderly care home residents. J R Soc Med. 2007;100(6):258–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/014107680710000608.

Jenkins C, Smythe A, Galant-Miecznikowska M, Bentham P, Oyebode J. Overcoming challenges of conducting research in nursing homes. Nurs Older People. 2016;28(5):16–23. https://doi.org/10.7748/nop.28.5.16.s24.

Maas ML, Kelley LS, Park M, Specht JP. Issues in conducting research in nursing homes. West J Nurs Res. 2002;24(4):373–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/01945902024004006.

Hall S, Longhurst S, Higginson IJ. Challenges to conducting research with older people living in nursing homes. BMC Geriatr. 2009;9:38. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-9-38.

Hubbard G, Downs MG, Tester S. Including older people with dementia in research: challenges and strategies. Aging Ment Health. 2003;7(5):351–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360786031000150685.

Goodman C, Baron NL, Machen I, et al. Culture, consent, costs and care homes: enabling older people with dementia to participate in research. Aging Ment Health. 2011;15(4):475–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2010.543659.

Schilling I, Gerhardus A. Methods for Involving Older People in Health Research-A Review of the literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(12). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14121476.

van Manen M. Phenomenology in its original sense. Qual Health Res. 2017;27(6):810–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732317699381.

Silva RV. Oliveira WFd. O método fenomenológico nas pesquisas em saúde no Brasil: Uma análise de produção científica. Trab Educ Saúde. 2018;16(3):1421–41.

Bartlett R, Milligan C. The development of diary techniques for research. In What is Diary Method? 2015(pp. 1–12). https://doi.org/10.5040/9781472572578.ch-001.

Snowden M. Use of diaries in research. Nurs Stand. 2015;29(44):36–41. https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.29.44.36.e9251.

Albine M, Irene Korstjens. Series: practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis. Eur J Gen Pract. 2018;24(1):9–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13814788.2017.1375091.

Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001.

Brasil, DE 27 DE MAIO DE. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária. Resolução da Diretoria Colegiada - RDC nº 502, 2021. Dispõe sobre o funcionamento de Instituição de Longa Permanência para Idosos, de caráter residencial. http://bibliotecadigital.anvisa.ibict.br/jspui/bitstream/anvisa/423/1/RDCn531_04. 08.2021_publicada06.08.2021_versão%20web.pd. Acesso em 5 de agosto de 2023.

Brasil. Política nacional de assistência social. Ministério do Desenvolvimento Social e Combate à Fome. 2004. http://blog.mds.gov.br/redesuas/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/PNAS_2004.pdf. Acesso em 5 de agosto de 2023.

Yoon MN, Ickert C, Slaughter SE, Lengyel C, Carrier N, Keller H. Oral health status of long-term care residents in Canada: results of a national cross-sectional study. Gerodontology. 2018;35(4):359–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/ger.12356.

De Visschere L, Janssens B, De Reu G, Duyck J, Vanobbergen J. An oral health survey of vulnerable older people in Belgium. Clin Oral Investig. 2016;20(8):1903–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-015-1652-8.

Volk L, Spock M, Sloane PD, Zimmerman S. Improving evidence-based oral health of nursing home residents through coaching by Dental hygienists. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(2):281–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2019.09.022.

Brito AACd, Silva JdVe, Holanda JMF, Souza RRMNd L. TCdOMKC. Vulnerability of institutionalized older people and social support in the perspective of the COVID-19 pandemic. Rev. bras. geriatr. gerontol. 2022;25(6):e220051. https://doi.org/10.1590/1981-22562022025.220051.

Shepherd V. Advances and challenges in conducting ethical trials involving populations lacking capacity to consent: a decade in review. Contemp Clin Trials. 2020;95:106054. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2020.106054.

Lee YA, Salahuddin M, Gibson-Young L, Oliver GD. Assessing personal protective equipment needs for healthcare workers. Health Sci Rep. 2021;4(3):e370. https://doi.org/10.1002/hsr2.370.

Organização Pan-Americana da Saúde. Módulos de Princípios de Epidemiologia para o Controle de Enfermidades. Módulo 4: vigilância em saúde pública / Organização Pan-Americana da Saúde. Brasília: Organização Pan-Americana da Saúde; Ministério da Saúde, 2010. 52 p.: il. 7 volumes. ISBN 978-85-7967-022-0.

Kitwood T. The experience of dementia. Aging Ment Health. 1997;1(1):13–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607869757344.

de Boer ME, Hertogh CM, Dröes RM, Riphagen II, Jonker C, Eefsting JA. Suffering from dementia - the patient’s perspective: a review of the literature. Int Psychogeriatr. 2007;19(6):1021–39. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1041610207005765.

Margari F, Sicolo M, Spinelli L, et al. Aggressive behavior, cognitive impairment, and depressive symptoms in elderly subjects. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2012;8:347–53. https://doi.org/10.2147/ndt.s33745.

McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005.

Rodrigo-Claverol M, Malla-Clua B, Marquilles-Bonet C, et al. Animal-assisted therapy improves communication and mobility among Institutionalized people with cognitive impairment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(16):5899. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165899.

Gènova-Maleras R, Álvarez-Martín E, Catalá-López F, NFd L-B, Morant-Ginestar C. Aproximación a la carga de enfermedad de las personas mayores en España. Gac Sanit. 2011;25:47–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaceta.2011.09.018.

Gioffrè-Florio M, Murabito LM, Visalli C, Pergolizzi FP, Famà F. Trauma in elderly patients: a study of prevalence, comorbidities and gender differences. G Chir. 2018;39(1):35–40. https://doi.org/10.11138/gchir/2018.39.1.035.

Larsen PP, Thiele S, Krohne TU, et al. Visual impairment and blindness in institutionalized elderly in Germany. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2019;257(2):363–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-018-4196-1.

Brasil. Câmara dos Deputados. Projeto de Lei nº 4.702, de 12 de novembro de 2012, aguardando parecer. 2012. http://www.camara.gov.br/proposicoesWeb/fichadetramitacao?idProposicao=559429. Acesso em 5 de agosto de 2023.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was supported by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (001), Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (PPM-00603-18), and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico Tecnológico (CNPq: 310938/2022-8).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors contributions were: Conceptualization, RCF and TMCR; Acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data, TMCR, AASA, TAA, FFT, RCF, AAS, VEG; Supervision, RCF, AAS; Writing – original draft, TMCR; Writing – review & editing, TMCR, RCF, AAS, VEG, KGNB; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study received approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. The participants signed a statement of informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ramos, T.M.C., da Silva Alves, Á.A., Apolinário, T.A. et al. Challenges to conducting research on oral health with older adults living in long-term care facilities. BMC Oral Health 24, 422 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-024-04204-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-024-04204-x